Introduction

In 2009, Patrick Debois introduced the concept of DevOps at the first DevOpsDays conference in Belgium, with the objective of bringing development and operations together. Over the last decade, we have seen how organizations transformed the way software builds are shipped, breaking down silos, automating pipelines and accelerating releases through Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery (CI/CD). These practices have since become the backbone of modern software delivery.

As of 2025, we stand on the edge of another transformation. The next frontier is no longer velocity but intelligence. Just as CI/CD pipelines became the abstraction layer for delivery, agents are emerging as the new abstraction layer for intelligent automation. The key difference is that DevOps solved the question “How fast can we deliver?” while agents will answer “How intelligently can systems reason, coordinate and adapt?”

While this blog draws parallels to the DevOps revolution, it is not about deployment pipelines. It is about the mindset and architectural shifts required to engineer intelligent systems. The comparison is about the nature of change: DevOps redefined release velocity, while agents will redefine intelligent orchestration across the entire software lifecycle.

By the end, you will see why agent-first thinking is not a passing trend but the foundation on which the next decade of intelligent systems will be built.

Why Agents Aren’t Just Wrappers

On the surface, AI agents may appear to be just another abstraction layer on top of APIs, but they represent something far more fundamental. With agents, the abstraction is not about scripting workflows but about embedding intelligence into them.

What are Agents

According to AWS, an artificial intelligence (AI) agent can be understood as a software programme that interacts with its environment, gathers data, and then uses that data to work towards predefined goals. While humans set the objectives, the agent determines the sequence of actions required to achieve them. For example, in a contact centre scenario, an AI agent might guide a customer through a series of questions, consult internal knowledge sources, and provide answers directly. Where necessary, it will also decide whether to escalate the issue to a human colleague.

It is important to see agents not as an add-on but as a new abstraction layer in system design. Just as CI/CD pipelines became the layer that abstracted away manual builds and releases, agents will become the layer that abstracts away repetitive orchestration and task coordination. This makes agents a foundational construct in future architectures, not just another tool.

Core Capabilities

The three core capabilities of agents are reasoning, autonomy and memory.

Figure-01: The core capabilities of agents

Reasoning is what drives decision-making in agents. By combining perception with memory, agents can apply rules or heuristics and choose the next best step towards a goal (IBM Agentic Reasoning). Unlike rule-based systems, they can connect signals that would normally be missed. For example, in anti-money laundering, an agent can link multiple alerts to spot suspicious activity more effectively.

Autonomy gives agents the ability to act without waiting for human instructions. They can start tasks, adapt when conditions change, and recover from failures while staying aligned to the goals set by humans. In incident response, this could mean filtering out false positives and escalating only when there is a genuine threat.

Memory allows agents to store and recall past interactions, making their decisions more context-aware and adaptive over time. Where traditional models treat each task in isolation, agents with memory can recognise patterns, retain context, and learn from feedback (IBM Agent Memory). In customer support, this means remembering a user’s earlier issues and shaping responses accordingly.

“Agents are not wrappers around APIs, they embed intelligence into workflows”

Reactive to Adaptive Systems

Traditional software systems are reactive, where actions are triggered by predefined rules in response to past events. For example, an e-commerce platform that flags a sales channel as fraudulent only after several customers have lost money is reactive. An adaptive system, by contrast, would detect suspicious behaviour early and intervene before the first customer becomes a victim.

Forrester identifies adaptive process orchestration (APO) as the next stage in enterprise automation. This approach combines deterministic workflows with AI agents and nondeterministic control flows, enabling systems to meet business goals, manage complex tasks and make autonomous decisions.

This adaptive capability is precisely where agents begin to reshape system design, moving beyond scripted automation toward intelligent orchestration.

“Adaptive systems act before failure”

Challenges and Limitation

Designing, building and deploying agents is not without challenges. Some of the key ones are:

- Reasoning – outcomes are probabilistic rather than deterministic, which makes them harder to predict.

- Memory – can drift over time, introducing bias or errors.

- Autonomy – requires strong governance, monitoring, and ownership to keep agents within safe limits.

- Safety and Alignment – critical to ensure agents act as intended and avoid unintended behaviour.

- Integration – fitting agents into enterprise systems can be complex and time-consuming.

- Resource Demands – high compute needs and reliance on skilled engineers can slow adoption.

From Service Mesh to Agent Mesh

Having looked at the shift from reactive to adaptive systems, the next step is to explore how such systems can be designed through the concept of an agent mesh.

Beyond Service Mesh

Microservices architecture allowed engineering teams to focus on business logic, while the service mesh handled network concerns such as load balancing and service-to-service (east–west) routing. The service mesh complemented microservices and improved the speed of software delivery, but both come with limitations.

Microservices introduce complexity, infrastructure overheads, data management challenges, east–west communication issues, and difficulties in debugging and testing. Service meshes, while addressing some of these problems, also add constraints in managing the control and data plane, particularly around configuration, monitoring and troubleshooting.

Though service meshes solved many operational challenges of microservices, they remain deterministic, rule based and reactive. An agent mesh offers a solution to extend microservices with adaptive intelligence, making them more efficient and capable of handling dynamic conditions.

Multi-Agent Systems: The Foundation

In reality, we will not have a single agent doing all the work. Enterprise systems will rely on many agents, each specialising in a particular task.

It is useful to briefly outline the core components of a multi-agent system (MAS) before moving on to the agent mesh. A MAS is made up of three elements: agents, the environment, and the mechanisms for interaction. Agents have the autonomy to carry out tasks, the environment is where those tasks are executed, and interaction mechanisms govern how agents communicate and collaborate to solve problems.

Interaction mechanisms include communication protocols, coordination methods and orchestration strategies. Protocols can range from Agent-to-Agent (A2A) and Agent Communication Protocol (ACP) to newer standards such as the Model Context Protocol (MCP) and Agent Network Protocol (ANP). Coordination determines how agents share information and assign responsibilities, while orchestration defines the sequence of actions required to achieve a goal.

Where MAS describes the foundational components and behaviours of agents, an agent mesh defines the architecture that enables these agents to work together in a scalable and reliable way.

The Core Layers of an Agent Mesh

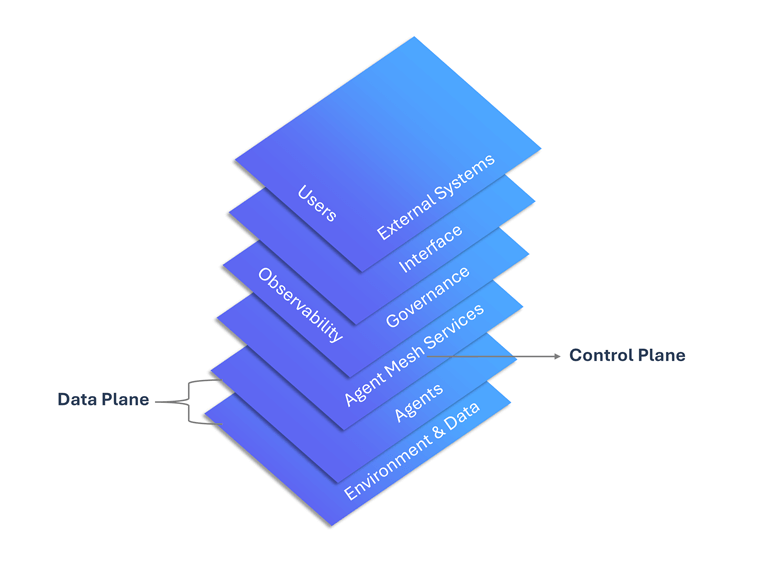

An agent mesh is an architectural pattern designed to govern, scale and manage the ecosystem of autonomous AI agents. While the exact implementation may differ across frameworks, an agent mesh typically includes several layers: the agent layer, agent mesh services, governance and observability, and the interface layer.

Figure-02: The core layers of an agent mesh

The agent layer consists of multiple agents, each performing independent tasks, using tools, and working towards specific goals.

The agent mesh services layer acts as the connective tissue of the agent mesh. It provides essential services such as orchestration, communication, registry and discovery to locate the right agent for a given task. It also offers memory to store and retrieve conversational history, task execution records and other details.

Governance and observability layer provides enterprise-grade controls required to manage and run complex multi-agent ecosystems. Policy enforcement covers rules, agent behaviour, data access and interactions. The mesh also operates with zero-trust security, where each agent must be authenticated and authorised. The observability stack enables the use of tools for advanced monitoring and audit logging.

The interface layer handles the points of contact where humans and agents interact with the mesh. These interactions may take place through end-user applications, gateways, APIs and other access channels.

“In an agent mesh, the control plane orchestrates, the data plane executes”

In an agent mesh, the mesh services layer forms the control plane, while the agent layer together with the underlying infrastructure makes up the data plane. This is similar to a service mesh, where the control plane manages policies and orchestration and the data plane handles network traffic. The difference is that in an agent mesh, the data plane includes the agents themselves carrying out tasks, making it far more context-aware and adaptive.

These layers make the agent mesh resilient to failures and adaptable to change, with support for human-in-the-loop interactions when oversight or intervention is needed.

The Need for an Architectural Shift

Now that we have outlined the key concepts of an agent mesh, building one requires a shift in system design. The design must support both deterministic APIs and extend to adaptive, goal-driven orchestration. Earlier, microservices were largely stateless, but adaptive systems demand context-aware agents, which has implications for shared memory.

Observability must also move beyond log collection. Systems need to analyse patterns, reason about outcomes, and trigger next steps. Governance should not be treated as a bolt-on; it has to be built into the architecture from the start.

Enterprises must also define clear system boundaries: the role of APIs, agents, and human-in-the-loop (HITL). Reliability depends on being able to reproduce outcomes consistently and designing safe fallbacks. Integration will still rely on APIs, but orchestration will increasingly be handled by agents in a more intelligent way.

Redefining Ownership in Agent-First Systems

DevOps blurred the line between development and operations. In the same way, agent-first architectures will blur the boundaries across product, engineering, data, and operations. The culture has to move from speed (DevOps) to intelligence (Agents), and trust will play a critical role in promoting software safely to production.

As a consequence, existing responsibilities will be redefined. Developers will build, orchestrate, and maintain agents. Product and engineering managers will frame goals as agent tasks and think beyond feature tickets. SREs will need to monitor agent behaviour and observability gaps. Data teams will continue to focus on curation, training data, and retrieval sources for agents. Security and compliance will extend their scope to embed governance, alignment, and auditability.

“DevOps redefined speed, agent-first will redefine intelligence”

Agent mesh architectures will also create new roles. These include assessing the risks of over-trusting autonomy, explaining decisions when agents act in unexpected ways, and developing new practices for observability, prompt or goal engineering, multi-agent coordination, and human-in-the-loop operations.

The culture around software delivery is shifting once again, and agent-first systems will demand shared ownership, new skills, and stronger trust across teams.

Conclusion

The DevOps movement reshaped how software was delivered by making speed and shared responsibility the norm. Agent-first architectures will bring a similar transformation, but this time the focus is on intelligence, adaptability and trust.

Agents are not wrappers around APIs; they introduce reasoning, autonomy and memory into system design. The agent mesh provides the architecture to make this reliable, governed and scalable. For enterprises, the implications are clear: system boundaries must be redrawn, governance must be built-in, and culture must evolve to distribute ownership in new ways.

The path will not be instant. It will require careful experimentation, stronger governance, and cultural alignment across teams. But those who start early will not only gain efficiency, they will set the standard for the agent-first era. This is not a passing trend, it is the foundation for the next decade of intelligent systems.